|

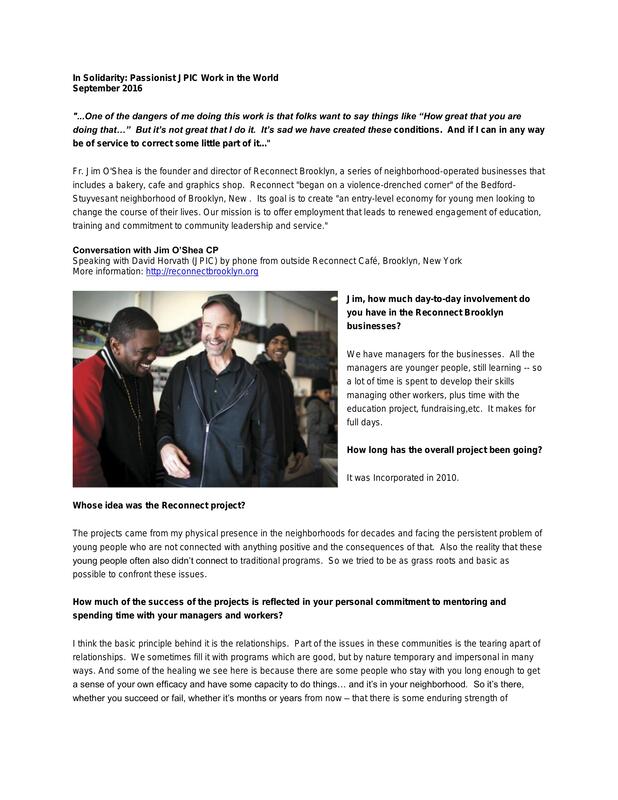

Solidarity news and reflections of interest to the Passionist Family "...One of the dangers of me doing this work is that folks want to say things like “How great that you are doing that…” But it’s not great that I do it. It’s sad we have created these conditions. And if I can in any way be of service to correct some little part of it..."  Reconnect "began on a violence-drenched corner" of the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, New . Its goal is to create "an entry level economy for young men looking to change the course of their lives. Our mission is to offer employment that leads to renewed engagement of education, training and commitment to community leadership and service." Fr. Jim O'Shea is the founder and director of Reconnect Brooklyn, a series of neighborhood-operated businesses that includes a bakery, cafe and graphics shop. Reconnect "began on a violence-drenched corner" of the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, New . Its goal is to create "an entry-level economy for young men looking to change the course of their lives. Our mission is to offer employment that leads to renewed engagement of education, training and commitment to community leadership and service." Speaking with David Horvath (PSN) by phone from outside Reconnect Café, Brooklyn, New York More information: http://reconnectbrooklyn.org Jim, how much day-to-day involvement do you have in the Reconnect Brooklyn businesses? We have managers for the businesses. All the managers are younger people, still learning -- so a lot of time is spent to develop their skills managing other workers, plus time with the education project, fundraising,etc. It makes for full days. How long has the overall project been going? It was Incorporated in 2010. Whose idea was the Reconnect project? The projects came from my physical presence in the neighborhoods for decades and facing the persistent problem of young people who are not connected with anything positive and the consequences of that. Also the reality that these young people often also didn’t connect to traditional programs. So we tried to be as grass roots and basic as possible to confront these issues. How much of the success of the projects is reflected in your personal commitment to mentoring and spending time with your managers and workers? I think the basic principle behind it is the relationships. Part of the issues in these communities is the tearing apart of relationships. We sometimes fill it with programs which are good, but by nature temporary and impersonal in many ways. And some of the healing we see here is because there are some people who stay with you long enough to get a sense of your own efficacy and have some capacity to do things… and it’s in your neighborhood. So it’s there, whether you succeed or fail, whether it’s months or years from now – that there is some enduring strength of relationships that are faithful to one another. It’s hard to describe to a funder because there is this idea that we try to fix things in two months or something. Even from a justice perspective of what we have done to destroy communities for centuries and that now we’re going to fix peoples’ lives in a month with some type of program. Obviously it is lot deeper than that and the healing takes longer, a longer term project. If you can use businesses that generate income and capital, and figure out how to build on those in the community, pull resources together, but recognizing that there are always going to be bumps.  How do you address funders looking for evidence and numbers-based outcomes to measure success? We’re very interested in what happens with these young people, which is why we look at the Education Project. In terms of the underlying human growth, success is built on relationships and a longer term. So we’ve hired 60-plus guys over the last few years and 71% keep working. So we take that to a funder. And most of them have never worked before and we consider the demographics of the neighborhood. So if that big a percentage of them continue to work, we can can make the link between having a place to learn how to work and their continued working. We hoping to get the same kind of numbers with higher education. Will you say more about the Education Project? Why aren’t more students choosing college? Why is there such a lack of engagement with something that is so accessible and that so clearly has positive impact on someone’s future. Why is it that people are obviously making such poor decisions with regard to that? Is it the simple answer that they just don’t care or they don’t want that or is it a much more complicated reality that we need to look at and to start rebuilding what education is meant to do and what it can do in someone’s life – intellectually and spiritually – and for their future? http://reconnectbrooklyn.org/reconnect2genius/ When we approach funders and the wider community, we want to show what neighborhood solutions might look like, as opposed to other types of interventions that have a lot of money put into them and aren’t necessarily successful. Ultimately what I would like to see with these projects is to add to the discussion about what is happening in urban neighborhoods and what other models there are. That this is a unique model – it’s unique, but it’s strange that it is, because it is quite simple. The biggest problem that everybody has is they can’t find jobs for guys coming home from jail, or haven’t ever worked. A simple solution is that instead of a million more training programs that you might develop businesses to learn how to work. It’s not that hard to figure out. But it’s a lot of work. Sometimes non profits don’t want to do that. It’s a lot of hands-on and you have to learn how to run businesses. What do you struggle with the most these days in your work in the neighborhoods, especially in a society that is so hurting and wounded?

On one level, I’m a Passionist, and not a business man. And the bulk of what I have to do is to help create successful businesses with people who also lack a business background. In some ways I really like parts of the work such as the entrepreneurship. But I am also working with guys who are trying to build their own confidence and trying to understand their own lives. So I think, how long before I can be replaced by someone who can take the whole thing to a different place? Another reality is that I’m a privileged white man leading an organization where everyone else is a person of color. And as a clergy person people give you a little bit of a pass. There is some discomfort there. In the beginning you don’t know if it will even take off. You have no money. Now you get to five years later and it is time to think about the future a bit more. You think about leadership and who to hand it on to. If you had to hire someone based on business experience, you wouldn’t hire me! But I was able to start it and get it off the ground, contacting foundations and forming a network. Now, how can that be expanded? o What practical challenge can you offer the Passionist JPIC family as we all live to seek a more undivided and faithful life? In any of our ministries and places we work, we can recognize the great disparity of human experience, even in just admitting that race has played such a role in how communities have developed and human beings have developed or haven’t developed, and taking some collective responsibility. One of the dangers of me doing this work is that folks want to say things like “How great that you are doing that…” But it’s not great that I do it. It’s sad we have created these conditions. And if I can in any way be of service to correct some little part of it... We collectively created these worlds and we continue to benefit from the worlds we created. We’re guilty bystanders. Sometimes we end with shallow conversations about what this is all about, leave it with good guy, bad guy, rich .people, poor people. That’s not the story. But it’s hard to avoid, because we continue to use the optic and like that story: we go in and help people. No, we’re not helping people, because we created the mess. Instead we’re helping ourselves to see what we’ve done and say “can I be a small part of healing that?” That’s a challenging conversation. So you see me doing this work on things I’m not necessarily prepared to do, while all of our national resources and wealth are going into other things, like buying more cops, more weapons. So Jim O’Shea is doing a good thing. Well no he’s not. He’s doing a fairly moderate job which should be done in a far more comprehensive way, with more resources.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed